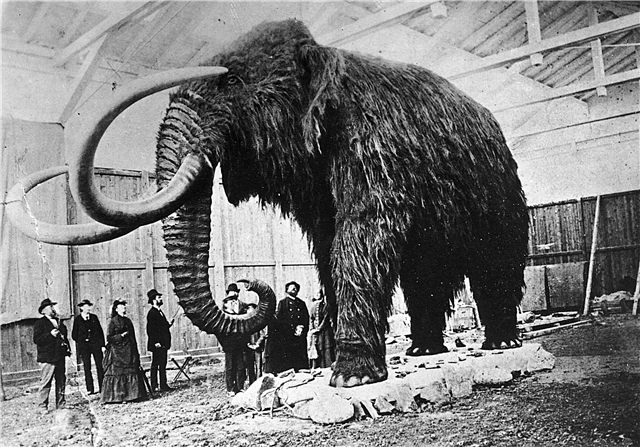

Desert plants deal with the problem of water in different ways. It sends the core root 10 to 30 meters down to find an underground source.

But how does a small seedling survive a long period of drought until its stem root finds water? This is one of the unresolved mysteries of the desert. Cereus blooming at night forms an onion, which serves as an underground reservoir. A creosote shrub, in search of water, sends roots over long distances, which at the same time emit poisons in order to kill any seedlings in its vicinity.

Beautiful annual plants that bloom in the spring and cover the desert with a beautiful colorful carpet do not possess such ingenious inventions for survival during a lack of water. How do they deal with the problem? They do not allow it to come to a lack of water. Their seeds contain inhibitory substances that prevent germination. With heavy rain, these substances are washed away and the seeds germinate and grow. Plants bloom and bring seeds for future plants.

To remove the restraint, the amount of precipitation must, however, be at least 13 millimeters; light rain is not enough. Seeds can, so to speak, measure precipitation, and if the rain does not sufficiently moisten the soil, so this would not be enough for the plants to live, then they just continue to rest. They do not begin to do what they could not bring to an end.

Cacti in the desert

In the desert, there are also fleshy cacti that survive a long dry period due to the fact that they stock up on water on rare rainy days. Some store water underground, while others store it in their thick trunk. So that these green trunks can absorb carbon dioxide and carry out photosynthesis, the respiratory openings, the so-called stomata, must be open. But this is dangerous, since valuable water evaporates in the form of steam. To reduce losses to a minimum, stomata remain closed during the daytime heat and open only at night when it is cool. In addition, in desert cacti, stomata are located in recesses below the surface of the trunk, due to which moisture loss is even more limited.

Poor desert rains rarely seep deep into the soil. Therefore, cactus roots are usually superficial and occupy a large area to absorb as much moisture as possible. Plants swell when water supplies are replenished, and shrink when water is consumed during dry periods. In many cacti, the leaves are reduced to thorns, which do not allow predators who want to bite the plant or drink from it.

The most impressive representative of desert plants is the giant saguaro. From late April to June, the tops of the trunk and branches are covered with flowers that look like huge bouquets of white flowers. Each flower opens at night and withers the next day. But each saguaro repeats this spectacle night after night for approximately four weeks, and produces approximately a hundred flowers. Because of its splendor, the flower was honored to be the state emblem of Arizona.

Birds, bats, bees and night moths feed on nectar and pollinate flowers. Fruits ripen in June and July. Bakers, coyotes, foxes, squirrels, agricultural ants and many birds eat fruits and seeds. Woodpeckers hollow out more nests in the trunks and branches than they need, but the plant heals its wounds with a protective cloth to prevent water loss, and many other birds later use the hollowed hollows, including baby owl, screaming owls and small hawks.

In the past, Indians used these pumpkin-like depressions as vessels for water. The woody ribs, which support the enormous weight of saguaros laden with water, served to build shelters and fences. The green giants also provide many juicy fig-like fruits that the local Papago Indians knock down with long sticks from the tops of trunks and branches. They make jam, syrup and alcoholic drinks from them. The Indians, like their chickens, ate seeds. The saguaro fruits were so important for the people of Papago that the time of their harvest marked the new year.